Official Review

Attempting to navigate Megalopolis through its narrative alone proves a dizzying challenge. Throughout its 138-minute duration, metaphor often supersedes traditional storytelling – alternating between Latin dialogue and direct Hamlet references. Adam Driver embodies the magnetic, playful Cesar Catalina, a visionary architect from the 23rd century possessing time-manipulation abilities, though this science fiction element serves more as atmospheric context than plot device. This extraordinary power draws the attention of Julia Cicero (Nathalie Emmanuel), daughter of his political adversary, who seeks to master Cesar's temporal abilities. Adding layers of complexity are the murder accusations surrounding our time-freezing architectural virtuoso, and an array of characters – portrayed by accomplished actors including Giancarlo Esposito, Jon Voight, and Shia LaBeouf – whose machinations center on securing and maintaining influence within New Rome's power structure.

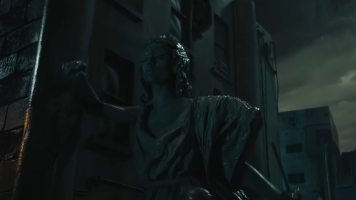

This neo-classical cityscape, blending ancient Roman grandeur with art deco Manhattan aesthetics influenced by visionaries like H.G. Wells and Fritz Lang, manifests through digital panoramas bathed in authoritarian gold. Despite its substantial budget, Megalopolis presents a curiously economical and two-dimensional visual quality, which inadvertently emphasizes the grotesque nature of its characters' opulent excess. Cinematographer Mihai Mălaimare Jr. employs a deliberately static camera approach, crafting precise compositions within a 2:1 aspect ratio that bridges the gap between television and cinematic formats. This conscious engagement with televisual elements materializes in Cesar's controversial relationship with ratings-driven broadcaster Platinum Wow (Aubrey Plaza), though the film ultimately transcends this aesthetic, suggesting Coppola's enduring reverence for traditional cinema. His portrayal of this futuristic society teeters on collapse, incorporating a distinctly skeptical view of modern technological conveniences and contemporary digital anxieties, from smartphones to contactless payments and AI-generated deepfakes.

Central to Coppola's technological exploration is Megalon, a mystifying, formless substance of infinite possibility. Created from the genetic material of Cesar's terminally ill spouse, this revolutionary material represents the architect's chosen medium for constructing his utopian Megalopolis. It embodies pure creative potential, a near-tangible manifestation of artistic vision. While the film Megalopolis operates through layered metaphors, the city itself represents an intensely personal dream, one that power brokers and financial authorities dismiss as mere fantasy – a familiar struggle for a filmmaker who has consistently faced obstacles throughout his career.

The film features multiple characters named Francis, yet it's Cesar, with his ability to perceive beyond conventional reality, who most clearly mirrors Coppola and his idealistic pursuit of unconventional filmmaking approaches. The ensemble combines both fresh faces and longtime collaborators, but the fleeting appearance of Coppola's sister Talia Shire carries particular emotional weight. In her role as Cesar's maternal guide, Shire emerges as an ambassador of cinema's more earnest era, seemingly encouraging her brother to maintain authentic emotional resonance amid the experimental energy of his latest passion project.

Megalopolis brims with such an abundance of conceptual layers that Coppola's ambitious fusion of different eras ultimately reaches a breaking point, collapsing in a calculated manner that initially puzzles but eventually erupts into an exhilarating cinematic spectacle. The narrative evolves beyond a mere cautionary tale about declining empires, drawing pointed parallels between Hollywood's systematic control and imperial dominance.

The mysterious Megalon substance serves as a creative catalyst for Cesar, enabling him to work with the same unrestricted artistic freedom that Coppola and his contemporaries George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg enjoyed during the transformative "New Hollywood" period of the 1970s. However, these references to cinema's golden ages transcend simple homage. Coppola's romantic vision necessitates a return to cinema's roots, incorporating silent film techniques such as blue tinting and iris shots during Cesar's moments of romantic remembrance or connection. These bursts of artistic expression pierce through the film's otherwise austere exterior. As these creative flourishes multiply, Megalopolis gains increasing humanity, positioning fundamental concepts like love and artistic expression as potentially world-altering forces. While this might initially seem idealistic, it reflects Coppola's enduring faith in America (echoing themes from The Godfather), even as he grapples with its apparent decline, raising urgent questions about potential salvation.

These personal reflections, however, cut both ways. Interpreting Megalopolis as a self-referential narrative inevitably invites consideration of the controversies surrounding its casting and production. Yet Coppola appears unconcerned with addressing any behind-the-scenes tensions. Instead, his focus lies in channeling his unique perspective – shaped by his experiences as an accomplished filmmaker, octogenarian millionaire, and vintner – into an impassioned warning about our current political systems' destructive nature. While the veteran director doesn't shy away from obvious references to contemporary political rhetoric, he maintains distance from explicit activism, preferring to let his artistic vision speak for itself.

His entreaties prove to be as enigmatic as his cautions, manifesting in truly unconventional yet groundbreaking forms. Just when Megalopolis appears to verge on unwarranted earnestness – marking Coppola's most heartfelt creation since his 1982 musical misfire One from the Heart – he transcends the conventional limitations of cinematic imagination entirely. At Cannes, this transcendence materialized through an unexpected appearance of a real-life actor engaging in dialogue with the on-screen Cesar. If there exists a method to jolt viewers from their passive state – whether temporary disengagement or the broader weariness of mindlessly consuming committee-approved studio offerings – this surely represents it.

The implementation of live elements during Megalopolis' IMAX release remains uncertain, yet this singular creative choice physically embodies the transformative themes that both Cesar and the film explore. From this point forward, Coppola's artistic vision becomes utterly captivating. The narrative evolves from a verbose, theme-explicit Shakespearean satire into a genuine meditation on cinema's boundaries and the constraints of physical and political frameworks.

As Cesar materializes his vision of a new world, it unfolds through multidimensional, kaleidoscopic imagery that challenges and virtually dismantles traditional cinematic presentation. Visual elements bend, undulate, dissolve, and grow. While Cesar's designs emerge in overlapping triptychs, the visceral reality of Megalopolis gradually materializes. The dramatic elements become more intimate, with tighter camera work enhancing the personal nature of the narrative. When conventional cinematic techniques like telephoto lens portraits are juxtaposed against bewildering digital landscapes, they create a simultaneously disorienting and mesmerizing effect. It represents an unattainable dream somehow rendered tangible by a visionary who perceives across temporal boundaries, offering us contrasting yet ultimately overwhelming glimpses of potential futures – both the path to salvation and the road to destruction.

At the heart of this deeply challenging yet immensely magnanimous vision lies the essence of love. (While several major releases at this year's Cannes explored similar themes – though notably absent in Furiosa's narrative.) This manifests not merely as an abstract philosophical concept, but as a profound celebration of familial bonds, shared understanding, and artistic collaboration. The presence of Eleanor, Coppola's wife and enduring creative partner, throughout Megalopolis' completion, and her tragic passing mere weeks before its premiere, adds poignant resonance. The film's closing dedication to her transforms into both a fitting memorial and a haunting testament to the work's ultimate self-realization: chronicling an artist in his twilight years, whose deep capacity for love enables him to momentarily suspend time's relentless forward march, while pursuing the creation (and spiritual transmission) of an audacious, revolutionary vision for humanity's brighter tomorrow. The result stands as an unprecedented cinematic achievement.

Verdict

Francis Ford Coppola's long-awaited masterpiece establishes challenging foundations that evolve into bold cinematic experimentation. A narrative exploring creativity, power, and artistic vision, Megalopolis emerges as an intensely individual creation, where verbose symbolism ultimately yields to astonishing visual metamorphoses. It represents the perpetual struggle of artistic expression, reimagined as a futuristic Roman saga in the 23rd century.