The book itself was empty – sorry to James Turner, co-director of The Plucky Squire, that we've revealed the secret – but that's kind of the point. The Plucky Squire is a game about discovering the story of hero Jot, preserving that story, and saving creativity, all to preserve the innocence and imagination of kids. In the game itself, it's a boy called Sam, whose favourite book is the titular tome, but in reality, we couldn't help but think of kids everywhere and want to protect that creativity that youth gives us – and that age can sometimes take away.

And we couldn't agree more. Even from our short time with it, The Plucky Squire felt like something Nintendo itself would make, even without playing it on Switch. The parallels to Zelda, in particular, are evident, but it's all done in such a whimsical, child-like way that pays loving homage to a particular green tunic-wearing adventurer. Jot's feather cap, brown boots, and simple design all fit the template for a kids' hero, one that the player can create a range of possible futures and storylines for outside of the one the book presents.

The Plucky Squire plays in both top-down 2D and 3D. The 2D sections all take place in the book itself, while the 3D sections see Jot jump out of the book and onto Sam's desk. We played through Chapter 6, which takes place in a mountainous region leading to a mining town in the book, while the desk is more space-like, with rocket ship art, alien stickers, and more adorning the surfaces. Every single sticker in the game is designed by a different artist or friend of Turner and Biddle. The parallels between the desk and the book in this level are clever, but the visual and thematic discrepancies are just the start of the relationship between these two worlds.

The goal of the chapter, and the main plot point of The Plucky Squire, is to get rid of the mechanical – the "anti-creative" as Turner puts it. Enemies throw tomatoes at Jot – kind of like how dissatisfied theatre audiences once threw tomatoes at performers — a really delightful touch that hammers home that fracture between the creative and mechanical. Progress in the book will be blocked by machine-like structures that use a completely different art style to the sketched-out, thick line art of the storybook. Gears separated the mountains from the mining town, and the only way to fix that was by leaving the book.

Almost everything Jot can do in the book, he can also do on the table. Sword slashes are identical, and of course, he has his own little spinning sword-slash. The hero can even throw his sword like a boomerang and call it back. On the page, perspective isn't an issue, either – because the 'world' is flat, Jot can swipe enemies that are technically a level above him, because that plane doesn't really exist in the book. You can't do that on the table, but you can attack in all directions. Eventually, you'll be able to buy new attacks and skills using the Lightbulbs you collect throughout the level, too.

Chapter 6's table does give us something new to play with, though – a jetpack. Turner told us not every single level will have a gimmick like this, but the more open structure, and theming, of the table for this level allowed the team to get creative. We had to save a little jetpack's dad – who is on one of the mugs on the table – by collecting the dad's three broken pieces, and this involved completing objectives or minigames.

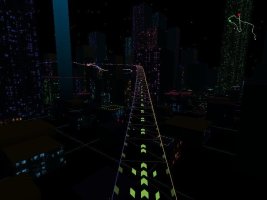

Because of the care and attention to detail, the 3D sections feel much bigger than they really are. You can jump into many of the drawings on the table – as long as those portals are there – and oftentimes you must to get to the next location. 2D action is not locked to the book either, which is demonstrated perfectly when we collected the last piece, which takes place in what looks like an '80s cartoon illustration set in an apocalyptic world.

What's great about these 2D worlds on the table is that they all utilise very different art styles. One long strip of paper looked like a child had scribbled all over it; others looked like night lights. But this '80s cartoon section goes a step further and throws you into a completely different kind of game – a side-scrolling shooter, complete with Jot buffing and becoming an '80s action man. The art style, mixed in with the fantastic arcade-style music accompanying the section, came together to create something magical to make us gasp. It speaks to that level of creativity and passion that All Possible Futures seems to be bursting with. Plus, we were promised there would be plenty more sections like this throughout the game. We can't wait.

Everything about The Plucky Squire filled us with child-like glee and captures the idea of finding "a new surprise on every page," as Turner put it. From the minimalistic UI to the story being narrated by British actor Philip Bretherton – perhaps best known for playing Alastair Deacon in the BBC show As Time Goes By – it feels like a story brought to life; a blend of Jackanory and projections of a child's imagination. We miss being kids with boundless creativity and a world of possibilities ahead of us, and The Plucky Squire made us feel like we'd recaptured that feeling. We're desperate to get another taste of it.

The Plucky Squire is planned for release later this year. How excited are you for this? Get sketching in the comments to share your thoughts.